The Arvada Rotory Club held a number of eye-glass and medical clinics in Guachochi, a 8,000 foot high community in Mexico. I went along and made a documentary titled

Medical Flights to Sierra Madre.

Each trip had its own personality and lots of adventure. One winter I had a lifetime experience and it made a really awesome back-story to my documentary and it happened just as written! Don’t skim, the text is carefully crafted for a special ending.

Years ago, Bernie Roland, an old college friend, called to ask if I was interested in flying with him to Guachochi, Mexico, to shoot a video. In this small community high in the Sierra Madre, they were flying small private planes into a short dirt-airstrip located at 8,000 feet halfway between Mexico City and the Texas border, just a few minutes away from the Copper Canyon. Jack Emery had recruited Bernie to help the Arvada Rotary Club with a humanitarian effort. I had always wanted to visit this area and eagerly signed on for the trip.

Over several years, Jack Emery and his wife Peg, along with other Rotarians, had made a significant impact on Guachochi, providing free eyeglasses and other medical care and raising funds for fire and trash trucks, as well as a school bus.

Inspired by the Emerys’ mission, Dr. Mitch Friedman offers dental services and supplies to those in need, and Rotarian Sharon Saquilon is working to establish the town’s first library.

Between 9 and 16 volunteers are flown or driven to Guachochi twice a year, with each volunteer paying his or her own expenses. To be successful, each volunteer trip requires meticulous planning throughout the year. Because the days are busy, the next day’s

plans are discussed between songs and toasts while socializing with the locals in the evening. After a short night, the team keeps going from an unexplained source of energy.

Thinking back, I can recall Jack Emery’s chuckle as he told me that those who came to Guachochi found something special. Only later would I realize the full meaning of his statement.

Our group of volunteers stayed at the Lima Hotel in Guachochi, Mexico. Some of us were waiting for breakfast with Jack and Peg Emery when Dr. Rod Hock returned early from his routine morning walk. I was surprised to see him back so early. Shivering, he said it was “just too cold out there.”

Dr. Hock is an avid outdoorsman from a high-country Colorado community. He and some of the others were planning to hike to the bottom of the Copper Canyon and back in one day—an ambitious goal even for the best of hikers. If Dr. Hock said it was cold, I was in no hurry to go outside, even though my cold tolerance was high. It was January, after all, and we were at 8,000 feet, but I had been sure Mexico would be a lot warmer than Denver. In fact, I had only brought my down jacket out of respect for Jack’s advice. My indifference to the weather would later nearly cost me my life.

We braved the cold to reach the large community center, whose two-foot-thick stone walls retained heat, keeping temperatures somewhat warmer inside during the night, but also making the building slow to warm again in the morning. To stay warm, the team kept moving. While the Rotarian team prepared for the onslaught of hundreds seeking medical care, I documented their process with digital video—a less active task that made me more susceptible to the cold.

Walking through the crude structures of adobe or masonry in the town was a constant reminder of the area’s impoverishment. An old dilapidated flatbed truck was jacked up for repair on the street, and pickups sped noisily by, ignoring stop signs. Wild horses ran through the streets without fanfare. I even saw a horse running down the road with someone holding the reins from the back seat of a car.

Approaching our medical center, I saw a large crowd lined up outside. Inside, the group of proud men, women and children offered images that most journalists would die for. Indigenous people sitting at the test instruments and rugged Hispanic people with their families presented a unique view of both native Tarahumara Indians and Hispanic Mexican cultures. Though the indigenous people wore a variety of clothing ranging from Nike to local Mexican dress, some wore no Western clothing. I saw one of them dressed in a simple loin cloth and sandals. Looking at his strong features and sensing the power of the man looking back at me spurred my curiosity to understand more about his way of life.

All the visitors showed patience and respect for one another, with no pushing, crowding or complaining, though the lines were long and the exams slow. Several of the local Rotarians had come to help with the eye charts and other exams, but there was only one optometrist. I asked Dr. Hock if there might be a way to speed up the process, but he set me straight: “This is the only eye exam that most of these people have ever had and might be the only one they will ever get!”

The Rotary team examined 170 people that day. Doctor Friedman had started oral surgery and eventually pulled 26 teeth. Every minute of the trip had been planned, and we were supposed to attend a celebration in our honor at 6:00 that night. However, it was close to 7:30 PM when I got back to the hotel after cleanup at the clinic. I thought the evening’s plans would be cancelled due to the late hour. However, our translator—a local dentist named Alfredo who was instrumental to the success of our trip—reassured me: “In Mexico, time is flexible.”

While we were in Guachochi, the locals held several parties and barbeques to show their appreciation for our work. Upon entering a rough exterior building front, we were immediately surrounded by a warm, inviting home. The locals brought homemade dishes, and there were toasts made and awards presented between the Arvada and Guachochi Rotary Clubs. Despite the language barrier, the bond between the two groups has continued to grow over the years. Everyone joined in singing songs around a bonfire, and the laughter lasted into the night.

As we reached the clinic the second morning, again hundreds of people were lined up, patiently waiting for the clinic to open. The children were very quiet, until some of the Rotary team members coaxed them to interact with Disney stickers.

I had told Peg that I wanted to see more of the lifestyles of those who depend on the Rotarians’ services. On the second day, she motioned me over: “Kent, this is the patient you’ve been waiting for.” It was a 13-year-old native Mexican girl with 11 diopters of correction. Her father said she tripped over things when she walked. She was going to see a big difference when she got her first pair of glasses.

The girl and her father, Melina and Pedro, spoke Spanish, so Alfredo helped make arrangements for me to visit their home an hour’s walk away. Peg encouraged me to go right away. It was after 1 PM and would probably take the rest of the afternoon. Preparing for the journey and wanting as little as possible to carry, I took off my jacket and put on my Banana Republic photo vest. I quickly checked my pockets to ensure I had all the necessary supplies: camera, extra battery, and extra tape.

The father and daughter had already left, joined by the mother with her infant strapped to her back. I jogged to get ahead of them to capture their faces. I think they assumed that I thought they were going too slowly, and they sped up even more. At various points, I stopped to shoot video, then had to run to catch up. These were Tarahumara Indians, who are renowned for their cross-county running ability. I had heard that they had been excluded from some US marathons because of their superior abilities. This pace was indicative of much of the journey. Outside town, the road narrowed, and we started following a well-defined path that cut through some fenced properties and continued down into a deep canyon. There, the trail became much steeper and less traveled. This region was abundant with deep canyons that eventually fed into the Copper Canyon, which is deeper than the Grand Canyon.

Finally, we reached the valley bottom, and there was a rock path to cross the river. My legs were burning and the path back up was steep. It seemed as if we climbed switchbacks forever before finally reaching the top.

The trails were rockier now and barely distinguishable. I looked for landmarks to find

my way back and even placed stones and rocks along the trail for markers. I worried that I wouldn’t make it back before dinner, and Alfredo and Jack would have to come looking for me.

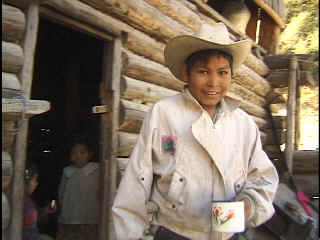

After at least three miles of hiking, when the sun was low in the sky, we reached the bottom of a wide portion of the deep gorge setback a short distance from the river. On the far side was a farmer’s field and the family home, a small, one-room log cabin with a hayloft above and three children timidly looking out. Pedro motioned for me to go inside, where Melina was waiting for me to videotape her. I had high expectations for my documentary, but thoughts of basic survival shortened this video shoot. I couldn’t communicate what I needed, and I didn’t have time to waste, so I quickly shot what I found.

Pedro’s son brought me a cup of water with sand particles floating at the bottom. I drank hesitantly, trying to leave the sand particles in the last inch of water. Feeling exhausted and knowing that the long return journey would be dangerous, I hoped for an invitation to spend the night. Eventually, though, Pedro’s son came over to me and pointed out the path back. Reluctantly, I began to slowly make my way back up the steep canyon trail.

The sun had already set in the valley bottom. Even if I made it out, I doubted if there was enough time to make it back. But I had no time to feel hopeless. I had to get going.

Though it seemed like an eternity, it probably took me about forty-minutes to reach the valley top. As I crested the valley’s ridge, I was greeted by a setting sun. Now there were three miles of hilly terrain before reaching the last deep gorge, and I had less than an hour of light.

As I tried to retrace my steps along the trail, I found to my dismay that everything looked different. I couldn’t find my landmarks or trail markers. I tried to track the footprints I had made coming in, but at times I had to follow different forks a hundred feet or more before finding them. Meanwhile, I was wasting the precious light I needed to cross the last gorge.

As I pushed forward, my lips were cracking and my mouth was dry. What I would have given for a glass of water! I hadn’t eaten since breakfast, but food didn’t seem important. My body had prioritized the essentials for survival: I felt the need only for water and rest.

The sun had set, and the light was fading. I sensed that the canyon gorge wasn’t much further, but I still doubted if I was even on the right trail. I could spend what precious time I had walking and try to descend to the bottom of the canyon and cross the river before dark.

Walking back up the other side without light would be difficult, but not as risky as going down. My other choice was to stop now, while there was time to build a shelter while there was light. I knew I could freeze to death without proper shelter or clothing, but I wasn’t mentally prepared to stay out all night, and I felt sure I could make it if I hurried.

As the light continued to fade, I came to another fork in the road. I couldn’t see well enough to determine which path to take. I got on my hands and knees, with my face inches from the ground, trying to spot a footprint. There was enough light to walk, but not to track.

I finally had to face reality. My gamble hadn’t paid off. Even if I could figure out which trail fork to take, there was no time to traverse the gorge. I needed shelter now! If only I had brought a flashlight.

Actual recording while treking back

As the light continued to fade, I came to another fork in the road. I couldn’t see well enough to determine which path to take. I got on my hands and knees, with my face inches from the ground, trying to spot a footprint. There was enough light to walk, but not to track.

I finally had to face reality. My gamble hadn’t paid off. Even if I could figure out which trail fork to take, there was no time to traverse the gorge. I needed shelter now! If only I had brought a flashlight.

I looked to see what natural protection the terrain had to offer. I had heard a story of native Mexicans killing a wandering journalist a year earlier, so I went a few hundred feet off the trail for isolation. When I couldn’t find some irregularity in the land that would offer protection from the wind, I picked a treed area that provided some insulation against the clear night sky. I found a large bush that helped somewhat to cut the wind flowing down from the higher ground above. I placed my camera on a nearby rock and began gathering pine needles. The needles were only about half an inch long, so it took a lot of raking with my fingers to accumulate the amount needed for a bed.

I stacked dead trees for a shelter wall. I got one side up about eighteen inches, but it still wasn’t enough. While the surrounding trees offered some protection from the elements, they also blocked out even the minimal light of the starry sky. Just venturing a few feet for shelter materials required me to feel my way back to my nest. The temperatures was dropping rapidly, and I was shivering. I wore only a turtleneck shirt and my netted photo vest. I was almost seduced by the thought of just lying down and going to sleep, but I knew that in my condition at this temperature, sleep would mean death. I had to summon the strength needed to save my life.

As my shaking intensified, I continued clawing pine needles into a pile to use as a blanket. The night was sucking my warmth and energy like a black hole. Strangely, my mind seemed detached from my physical struggle. I recognized that I might not survive and that if I died in the night, off the trail and covered with pine needles, my body might never be found.

As I sat contemplating what had gotten me into this situation, I saw what looked a flashlight beam from someone walking in the far distance. With difficulty, I yelled to them.

They didn’t reply. Even if they had heard me, if they weren’t part of a search party, they probably would avoid a stranger in the night.

I had a critical decision to make: Should I strike out and try to reach them or stay with my partially built shelter? Basic survival theory dictates that you should stay with your shelter. But it also says to build a fire, and I didn’t have any matches. I pondered my choices. If I left my shelter, I would probably never find it again. On the other hand, I didn’t know if my shelter would be adequate to protect me from the cold. I was also worried about the harm that might come to those looking for me in the night if I didn’t make the effort to reach them as well. Another benefit to getting moving again was that it might warm me up. With my decision made, I reached for my camera and started out towards the light, calling into the night.

After a hundred yards or so, the light disappeared. Now I’ve lost both my shelter and my chance to be rescued, I thought. But then I heard a car horn. Maybe the search party had come with an SUV to find me. There was just enough starlight to see a path through the trees but not the trail.

I started back in a different direction to try to find the main trail, where I thought the sound had come from. I yelled several times but heard nothing. Then, as I headed uphill, I began to hear dozens of horns honking. I turned around and saw a line of lights along the horizon. Dazed by hypothermia, I thought the search team had parked along the canyon and turned on their car lights to guide me home.

Then I realized the lights and sounds were coming from Guachochi. They seemed close because I was right next to the canyon that separated us. The town looked less than a mile away, but in reality it was unreachable. Without a flashlight in this darkness, I’d never get across that canyon.

Later on treking back

Entering the house

Then I saw the light of a nearby house window through the trees. It looked warm and inviting. This could be my salvation. However, I knew I needed to approach cautiously, because I was a stranger and I didn’t speak Spanish. I might even be shot as a prowler. I hoped the inhabitants might have heard that I was missing over the radio. If they addressed me in Spanish, I could say “no bandito, no bandito.” I had to cross a barbed wire fence to reach the house, and my apprehension increased. Now I was trespassing.

Within a few feet after crossing the fence, I could tell I was in an idle cornfield. I brushed against dried corn stalks and each step sounded as if it had smashed hundreds of cornflakes. I was concerned that the residents would hear this racket and become frightened.

It was dark, but finally a dark shadow in front of me turned out to be a house.

I was concerned that my noisy approach had alarmed the residents because the lights were out. Had they turned them off because they might have heard me coming? Would they shoot first and ask questions afterwards? Or was it coincidence that they had gone to bed just as I arrived? Carefully, I approached the porch and yelled out my arrival, “Anyone home?” No answer. I walked up onto the wooden porch and with my hands identified two doors facing each other in a recessed alcove. I knocked on the door. No answer. I yelled, “Anyone home?” There were no sounds to be heard.

I took my camera from my shoulder and turned it on. By turning it around, a dim light from the viewfinder radiated back out the eyepiece. I discovered a padlock on the door. Feeling around this alcove, I discovered a crude ladder constructed out of round poles that went up to an attic. I didn’t feel right going up there. That would be intruding. I called out once again, without a response from anyone.

Without considering the attic as an option, I had only one other option, to break in. It still didn’t seem right, even though it was a life or

death situation. I pushed hard on the door, but it wouldn’t open. I decided to explore. While circling the house, I felt part of the house or roof had collapsed. Then, around the corner, I found two exterior windows about five and a half feet off the ground. Both had been broken out. Again, I used my camera’s light to peer inside. I could barely identify straw on the floor…a definite bed. Then I heard an animal moving about inside. It sounded about the size of a large cat, but that’s not what it was.

The house’s walls felt solid and most likely were adobe or masonry. This mass would surely provide a warmer shelter than the outside. The entire house appeared to be falling apart, except for the doors keeping me out. At this point all I could think of was getting inside and out of the cold. I would just have to deal with whatever was in there.

To start, I placed my camera on the wide windowsill In my exhaustive state, I struggled to make it up into the window. I heard an animal scamper about. I finally stepped timidly onto the straw. The floor felt unstable, shaky at best. Remembering that the roof had caved in the other side, I knew it was possible that the floor could collapse too.

To be cautious, I rolled out on the straw with my entire body instead of stepping onto it. Spreading my weight over a larger area would places less concentrated stress on any failing floor structure. I stayed just in front of the window to further minimize my risk. I felt around and determined that there was considerable depth to the straw, but the entire support was moving. I shook while burrowing in and took some time to carefully cover myself with another eight inches of straw, including my head.

There was dirt mixed with the straw, and I could feel it all over me—in my mouth, ears, and hair. The straw beneath was excellent insulation, and my back was already enjoying the warmth. I laid there giving thanks to God. It felt so good to relax and enjoy this blissful cocoon. I was already halfway to my long-awaited dreamland when I felt something bite my foot.

What happened inside the house

My leg reacted automatically with a kicking motion, and I felt a small creature being thrown off. It bounded back, chewing within inches of my ears, and I knew that it would bite. Though I was bigger, I feared it would take a bite out of my ear. My heart was pounding as it circled me. Its weight suggested that of a small cat. I had heard that rats got that big in Mexico. Had I invaded its nest? After half an hour, I heard it scamper up what sounded like a long pipe, and then it was gone.

Now there was finally peace, and I could relax again. My mind began drifting, and then I came back to reality with the sounds of dogs barking. It took me a while to remember where I was and why. The dogs sounded close. It must be a search team. I didn’t want to leave my warm bed, but if I didn’t, the search team might go all night looking for me.

I carefully laid back the layers of straw so I could reposition them if I needed to return. My skin met an ice-cold wall of air. The straw created such a tight impression around me that it was difficult to get out. After carefully moving into the window, I jumped to the ground.

I heard dogs barking nearby and saw was another moving light. I yelled loudly, “Here, here!” No answer. The light was still moving and the dogs still barking. I repeated the call a second time, but less eagerly. I knew that a stationary light can sometimes give the illusion of movement. The next day, I would realize I was seeing the tops of Guachochi’s streetlights above the backside of the far hill, and the dogs were barking from their yards across the gorge.

I began to shiver and climbed back up into the window. I slipped into my cocoon and closed the straw lid. The dirt mixed into the straw got into my eyes, and it hurt. I needed water to flush my eyes, but there was none. I couldn’t even rub them, because my hands and face were dirty. I pulled my upper eyelid over the lower one to dislodge the dirt. This did the trick well enough.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t replace my straw covering as well as it had been initially. I continued to fuss with it, Though my back warmed again, my front still felt the cold. . I was directly in front of the window, and this location was particularly susceptible to waves of cold air.

I decided that I needed to build another cocoon further from the window. Once again, I struggled up and began to relocate my nest. The straw wasn’t as good there, but since the outside air wasn’t blowing directly on it, it was still an improvement. Finally, I was able to rest and my consciousness found a place between waking and sleeping for a few brief moments.

Then I heard two familiar objects sliding back down the pipe, and soon the two critters

were eating around me, one near my head, and the other near my feet. For a long time, I feared them chewing on me. My thoughts blurred in and out of consciousness.

Some time later, I heard loud, hollow footsteps stamping across the front porch pounding on the front door.. Someone was just outside and I heard the thump of someone placing their shoulder against the door. My heart raced. Someone was trying to get in. I kept quiet, afraid of being discovered or attacked. Whoever had come climbed the ladder into the attic and soon fell silent. Half an hour later, they went back down and walked off the porch, and I heard the sound of vomiting in the front yard. Then there was silence again.

Meanwhile, inside, my critter friends were still trying to intimidate me. The nuisance of their presence seemed insignificant after my last visitor. They were burrowing holes in my straw bed, allowing the cold to penetrate. I was continuously searching my cocoon for the latest critter hole to stuff.

Whenever I started to doze, my body temperature would lower, and I would start shaking again. This cycle repeated throughout the night. I was so cold on my top side that I wanted desperately to roll over to let the straw warm my chest. However, moving would have destroyed all the effort I had made in positioning my straw blanket.

Later, I again heard heavy footsteps on the front porch, and then someone forcing the front door. I heard the screech of a failing door latch. Ignoring the unstable floor, I flew out of my cocoon and found a table to lodge against the door. I felt around the room for a weapon but found nothing.

I stayed still. There was silence. Whoever was there had heard me. Were they waiting? Had I scared them off, or were they coming around to the open window? My heart pounded.

After half an hour of silence, I got back into my straw cocoon. I wasn’t sure if my shaking was more from cold or fear. Eventually the shaking subsided, but I still didn’t feel safe. Finally I was back in my cycle of dozing and waking from body shakes. This was truly the longest night I ever experienced. I’m not sure how long I dozed, but eventually it began getting light. I waited a long time, because I wanted the sun to warm the air before I got up.

Finally, I popped my head out of my cocoon ready to leave. It wasn’t morning. The light had come from the moon rising. I remembered it had come up around midnight a couple of days earlier. So my longest night had only begun. I heard something outside and looked through the window. In the moonlight, I saw burros in the yard. The second intruder must have be a burro.

Feeling more at ease now, I spent the rest of that night battling the little critters in my bed and hypothermia. Eventually the morning did come, but I waited as long as I could so that the temperature outside wouldn’t be too cold. It was about 7:00 AM when I decided to set out, moving quickly to generate heat. I shot some video of this memorable budget motel before leaving.

After finding the trail and a short walk, I could see I had traveled right up to the last canyon. It took me about an hour to finish the last leg of the journey through the canyon and back into town.

On the way, I saw search planes flying. I supposed they were still looking for me. I had to let someone know I was okay as soon as I got into town. One of the rescue team would probably give me a ride back to my hotel.

But I didn’t find a ride, nor did I see any of the search team. I had to walk the full distance back to the hotel, not knowing whether anyone would be there on account of the search.

As I got closer to the hotel, I could see our group inside. When I opened the door, they welcomed me, and I drank several glasses of water. Then I apologized for having ruined their previous evening.

They were puzzled. “What do you mean? We thought you were spending the night with Pedro.”

Everyone wanted to hear the whole story. When I finished, the others pointed out that it was remarkable that I had found the house. “How did you know it was there?”

Without thinking, I replied, “It was the light, of course. If it weren’t for the lights, I wouldn’t have survived the night.”

Then it dawned on me. My primitive sanctuary had no lights. But I knew I had

seen a window lit in the dark, and the house was right where the light had led me. The more I thought about it, the more I realized how miraculous all the interdependent events of the night had been. It might have seemed like the night from hell, but each distraction had actually kept me from falling asleep before it was safe. My gut instinct had kept me from going into the attic and had guided me away from contact with one of the night’s intruders. Even the pesky rats and unknown visitors had played a role in keeping my adrenaline pumping and keeping me awake. An uneventful night would have allowed me to drift off into a blissful sleep that I would never have awakened from. The night couldn’t have been better choreographed for keeping me awake and alive.

Jack had told me I would find something special at Guachochi, and he was right. In addition to surviving, I received several other gifts. I had always wanted to see the Copper Canyon region. I had always wanted a “National Geographic” adventure. This trip combined all three into an incredible experience. I would never have planned it, but it is one of the best I have had.

When I have interviewed the Rotary Club volunteers, most have told me how Guachochi has changed their lives. More than doing good deeds, what has affected them is giving of themselves, making a difference, being appreciated for their effort, and at the same time building personal relationships with our Mexican neighbors. This is more than talk; I could sense their karma having a serious glow overflow. It’s as if they had just flown back from Mr. Roarke’s “Fantasy Island.” The only difference is that Jack Emery is for real and anyone can take this trip.